Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 6: Food and the Arts.

All contributors to Vittles are paid: the base rate this season is £600 for writers (or 40p per word for smaller contributions) and £300 for illustrators. This is all made possible through user donations. Vittles subscription costs £5/month or £45/year ─ if you’ve been enjoying the writing then please consider subscribing to keep it running and keep contributors paid. This will also give you access to the past two years of paywalled articles.

If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or subscribe for £5 a month, please click below.

European museums and galleries can often feel alien and lonely to those who aren’t used to them. At least that is how I felt, when I visited them in my mid twenties for the first time. There were beautiful things everywhere, but I felt confused in these authoritative islands of glass, where looted beauty was exhibited as if to re-establish cultural control. I remember cowering under large canvases of imperial sea voyages and flitting around nervously until suddenly, something – an elusive Modigliani of a sad man sitting in an armchair; a rough sketch by an artist that illuminated a youthful earnestness – felt worthwhile. If intimacy is so rare in these spaces, it is unsurprising that when these gallery walls dissolve, it is noted with a success akin to being revolutionary. Take the instance of Thai artist Rirkit Tiravanija serving thai curry and rice to an audience in his 1992 artwork Untitled (exhibited in different iterations since) so viewers could be ‘within the artwork’ instead of outside it. Tiravinija’s work was celebrated widely even though and especially because it did something natural and instinctive. Because it brought undecorated interaction into the gallery’s tall, white walls.

Today, food is often the way to change the dynamics of art making and viewing. Since eating and cooking are approachable things, it is claimed that the quotidian humanity infused within food is the reason these artworks matter. Even so, my own favourite food as art is the one that resists this easy translatability — like when the Nigerian chef and writer Tunde Wey asked white diners to pay 100 USD for a piece of chicken in his dinner series Hot Chicken Shit as an “outrageous solution to the outrageous problem” of gentrification in the US. Or several instances of the artist Rajyashri Goody’s work, which destroys the caste hierarchy of food in India and takes back from dominant-caste violence on Dalit communities the joy of food as a right.

In today’s compilation, five writers think about five artworks in the genre of food and meals as art. Their arguments are as diverse as the artworks they pick, looking at how food is used to interrogate dominant status-quos, and when food is used as a tool for resurrection, bridging divides between the world inside the gallery and the one outside it. As these short essays exemplify, food in and as art is a vast, expansive world, and the works made within it can take several forms and aim to accomplish different things, with little clasping them together aside from the fact that they invoke food as a part of their process or result. Even though the artfulness of food seems to be most discussed when it is the babyish delights of the rich (like white-ribboned 300 dollar baguette bags), both food and art are really meaningful when they resist their most commodifiable tropes. And especially when they divert from that painful tendency to morph wonderful, everyday things into inaccessible luxuries, insisting that these are the only cases in which food, or anything else, becomes art. SD

A restaurant can be art, but can an artwork create community?, by Daniel Neofetou

In September of 2021, I attended a friend’s birthday dinner in the garden of a restaurant in Stoke Newington. It was in the early days of our collective emergence from over twelve months of pandemic restrictions, and every social event still seemed infused with a deep sense of conviviality borne of people relishing face-to-face human contact. The meal itself, however, was probably one of the most underwhelming I have ever had. It was a three-course set menu, with a courgette and green bean salad as a starter, a main of rice with fresh herbs and caramelised onion, and a panna cotta and mixed-berry coulis for dessert. It was ostensibly incredibly cheap, at £7.50 per head, but the portions were smaller than airline food and, egregiously, the rice was so undercooked that it was crunchy. The restaurant, however, was not simply a restaurant. Instead, it was an artwork entitled Shamiyaana by the Karachi-born, London-based artist Rasheed Araeen, first exhibited at the 2017 Athens documenta.

The notion that a restaurant can also be an artwork might seem strange to people not well-acquainted with the art world, but it should be mundanely familiar to those that are. The first well-known examples of restaurant meals being presented in an art context were probably Daniel Spoerri’s Restaurant Spoerri in Düsseldorf, founded in 1968, and Gordon Matta-Clark, Carol Goodden and Tina Girouard’s FOOD, which existed in New York’s SoHo from 1971–73. These were restaurants run by and for artists, rather than explicitly artworks themselves, but these categories were decisively conflated in the early 90s, when Rirkrit Tiravanija’s series of canonical relational artworks commenced with pad thai (1990); here, the artist cooked and served food for visitors to the Paula Allen Gallery in New York. These works, and works like them, always seem to rest on two central ideas: the (mostly implicit) idea that a meal becomes art rather than simply a meal because it has been prepared or commissioned by an artist, and the (explicit) idea that the object of the artwork is to bring a community together.

I won’t go into the first assumption at length, but it does raise the question of whether food can be appreciated as art qua food. Meals in an art context are not removed from their functionality in the world to the extent of a ready-made or found object; one cannot urinate in Duchamp’s Fountain (without getting kicked out of the gallery) but Tiravanija’s pad thai was there to be eaten. Nevertheless, there is the sense that food in an art context is primarily ‘interesting’ insofar as it is afforded the status of art, tacitly superseding its status as mere food. An interesting corrective here is the conception of ‘Kochen als Kunstgattung’ – which translates as ‘cooking as an art form’ – that the avant-garde filmmaker and keen chef Peter Kubelka has been propounding since 1967. Kubelka does not think cooking needs to be validated by art, arguing instead that food is ‘the mother of all arts,’ capable of informing and illuminating all other artistic practices.

As for the notion that food in an art context serves to bring communities together, this was true in the case of the interventions by Spoerri and Matta-Clark, Gooden and Girouard, which fostered and were completely embedded in collaboration between artists. In my personal experience, this has also been true of culinary projects within pre-existing DIY art scenes, such as chats cafe, run by Leah Walker, Berry Patten and Dannie Russo, whose residency at the project space Jupiter Woods in London’s South Bermondsey is for me inextricable from memories of the summer of 2018. However, in terms of works which are in commercial galleries or commissioned by international art festivals, this aim becomes the ostensibly more noble one of creating a community. According to Araeen, this was precisely the intention of Shamiyaana. In an interview with the Guardian promoting the restaurant, Araeen used terms which made it sound more like a community centre, affirming that with the project he intended to cultivate a space for ‘making, reading, playing, eating together and talking together’.

Now, unlike the blue-chip gestures of artists such as Tiravanija, Araeen has at least attempted to extend the reach of Shamiyaana beyond disparate art-world punters. In its first iteration as part of documenta, Shamiyaana was located in a central square in Athens, and provided free meals indiscriminately at a time when Greece was at the centre of the migrant crisis; in its location in Stoke Newington, free takeaways were given to people from the neighbourhood.

Yet, in both instances, Shamiyaana could be accused of tacit complicity with forces which dismiss or even erode already-existing communities. The Athens documenta was widely criticised for taking advantage of low wages and free or very cheap buildings eagerly proffered by Greek institutions, with little regard for the city itself. In an interview with Yanis Varoufakis, the curator and writer iLiana Fokianaki recalled that invigilators were ordering hungry Greek pensioners to give up their seats to students when they were deemed to have occupied them for too long, because Shamiyaana was, according to invigilators, ‘not a food bank but an artwork.’ And in the case of Stoke Newington High Street, the road has undergone intense gentrification in recent decades. While it was definitely not the intention of Shamiyaana to hasten this process, it begs the question of why an imposed artwork-restaurant might serve the function of bringing a community together better than local eateries which are already there.

Here, we might recall Kubelka’s notion of ‘cooking as an art form’ and ask whether the intersection of food and art praxis should occur at the point of artistic production at all. Instead, perhaps we should treat food as always-already art, and thus the contextualisation of food as art – that is to say, its appreciation as an aesthetic phenomenon in a particular historical and cultural context – should occur at the point of reception. And we might conclude that this work is already underway, and has been for quite some time, under the name ‘food criticism.’

Ceci n’est pas un cafe, by Rachel Karasik

I became disillusioned with the art world early on in my curation degree. Between lectures with titles like ‘The Death of the Country House’ (more of a lamentation of a bygone era than a critique of colonialism) and a brief weekend job invigilating at a famous gallery that wouldn’t let you speak or sit down during shifts, I quickly developed the jaded opinion that while anything can be art, not much art is good and, like with many creative industries, what is good is not necessarily what succeeds. By the end of my degree, I’d distanced myself as much as possible from the art aspects of my curriculum, finding solace in my love of food and convincing my lecturers to let me write about Come Dine with Me for my dissertation.

In 2012, a year after graduating, I was working far from the art world in social innovation and very much figuring out what it means to be an adult. Some colleagues invited me to see Jeremy Deller’s retrospective, Joy in People, at the Hayward Gallery in London. Deller, a Turner-prize-winning English conceptual artist, creates work which often focuses on the social and political, frequently collaborating with communities to create installations and performance pieces that celebrate and honour the histories, as well as the playfulness and melancholy, of everyday people.

Valerie’s Snack Bar sat in the middle of the gallery space, like a set for a play, brightly lit and filled with visitors milling around, sitting in booths or queuing, while a gallery assistant served complimentary mugs of black tea (with milk or sugar) from behind the functioning counter. Framed by wooden posts, a big glowing sign above beamed ‘Snack Bar’ and beckoned visitors into the installation. Classic red plastic bucket seats bolted to the floor, four to a table, filled the compact front, while behind the counter, where the tea was served, neon handwritten signs shouted the imaginary menu specials of the day. The installation would have been inherently familiar to anyone who has stepped foot in a British cafe, but was uncanny in its placement within a vast gallery space. I was instantly taken, and the story behind the piece made me love it even more.

Created as part of Procession, a commission for the 2009 Manchester Art Festival, Valerie’s Snack Bar started as a float in a parade celebrating ‘public space and the people occupying it’. Sitting alongside smokers, carnival queens and Big Issue sellers carrying union-style banners, Deller’s work was an almost life-sized recreation of a real cafe located in Manchester’s Bury Market (stall 49, for those interested) which was then hoisted onto the back of a lorry, filled with regulars who joyfully waved to onlookers, and driven through town. Apart from the fact that this piece of art was three-dimensional and dared to take up a large share of the gallery space, it celebrated the cafe as an inherently positive part of the social fabric of a city, inviting visitors to become part of the work.

I had seen art depicting everyday cafes and social dining spaces many times before, mostly in paintings – the isolated diners in Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks; Toulouse-Lautrec’s bustling swirls of absinthe-soaked cafe dwellers. I wrote an essay at university about a painting depicting a man gruesomely devouring a fish at a restaurant akin to Goya’s Saturn Devouring his Son. The cafe or dining space is secondary to the characters and actions within these pieces – a backdrop that in turn reflects the moral or social standing of the scene. Meanwhile, Deller puts the cafe front and centre with Valerie’s Snack Bar, both literally and metaphorically. In its original form in Procession, it, and its regulars, were the queens of the parade, and in its static form in the gallery, the piece invites visitors to celebrate and experience the cafe as a cultural artefact in and of itself.

In the hands of the wrong artist, Valerie’s Snack Bar could have easily felt like a parody of working-class culture for the delight of the artistic elite, but instead, Deller’s brand of ‘social surrealism’ resurrected a fragment of daily life into the gallery, familiar in its textures even though it was far from the din, smells, and bustle of its actual locale. Deller is an artist known to be inherently collaborative and political, one who embeds humanity in his work. With Valerie’s Snack Bar, and indeed the entirety of Procession, Deller centred the people and places that make up communities, and it’s a piece that I’ve referenced and returned to again and again in the decade since.

As I wandered around and through Valerie’s, sipping my tea and waiting for a spare booth, there was a buzzing energy made up of chatter, slurps and excitement at being granted permission to climb into, and become part of, a piece of art that felt so familiar to anyone who had even eaten a fry-up.

Wrapper Resurrection, by Ruby Tandoh

The first time I saw Michael Rakowitz’s work at the Whitechapel Gallery in east London, it felt familiar, even though I didn’t know what I was seeing. His work included a reconstruction of wall relief panels from an ancient Assyrian palace – the Northwest Palace of Nimrud – in a colourful, textured papier mache. There were figurines, pots, coins, urns and votive objects, each one a small riot of colour. These works, which formed part of Rakowitz’s ever-evolving project The invisible enemy should not exist (2006–), were reimaginings of treasures looted or destroyed in Iraq. The artefacts were made not from stone, metal, clay or wood but from ephemera: scraps of print media and, very often, food packaging. Here was a Maggi logo; over there a glimpse of a date syrup can. Fragments of Arabic script stuttered across the collaged surfaces. The gallery became a resurrection of looted artefacts through the visual language of the supermarket.

Even when it is doing the job it’s supposed to do, food packaging is seldom just itself. In Rakowitz’s visions of a lost Iraq, wrappers are evocative fragments of lives half remembered and others that could have been. As Iraqi Jews living in Baghdad, Rakowitz’s grandparents were born into a dynamic community that was quickly dispersed at the onset of the first Arab-Israeli war. They made their way first to Mumbai, then eventually to the US, where they settled in Long Island. Rakowitz’s relationship to his own history is disjointed: he is both Arab and Jew, part of an Iraqi family living in the US in the wake of the Iraq War. There is longing here, as well as heartbreak and futility; as his mother shared with the New Yorker, in his work Rakowitz ‘tries to bring forth something that is dead’. One of his largest resurrections, May the arrogant not prevail, is a reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate: once a processional route into ancient Babylon, it stands in what is now Iraq. Rakowitz’s miniature Ishtar gate is five metres high and six metres wide, the shimmering blue bricks of the original fashioned from hundreds upon hundreds of pieces of Arabic Pepsi and bottled water labels. The gold detailing that traces the edges of the arch is now created from Lipton Tea packets.

This resurrection isn’t just about the splendour of the gate itself but also about what has been lost in translation. The original gate was constructed before 500 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar II. It was then lost to history, before being excavated and partially, poorly rebuilt in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin in the early 1900s. (Germany has since declined to repatriate the ruins.) In the 1950s, a small reconstruction was erected once more near the ruins of Babylon, though by the turn of the century this too had been misappropriated, becoming a backdrop for photos of American soldiers stationed on a nearby military base during the Iraq War. Rakowitz’s gate is a reconstruction many times over, made from food packaging that was sourced from Arabic stores in the same Germany where the original ruins are being held captive. Approached from the front, this structure is spectacular. From the back, it is unadorned, rickety, its structural beams showing and its paper-thin veneer exposed for what it is. ‘It’s performance,’ Rakowitz has said of his work. ‘It's the projection of magical meaning onto objects.’

By dressing up ancient monuments in the wrappers of daily diasporic life, Rakowitz unveils the authority of the everyday. He shows that especially in times of war, especially when far from home, even inexpensive, mass-produced foods can take on an other-worldly aura. It isn’t that food packaging is uniquely meaningful: we can find meaning anywhere, but very often this ‘anywhere’ is the home – where we start from – and the ordinary mess it contains.

‘Please, take this’ by Louis Shankar

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991) is an esoteric, shape-shifting sculpture: a pile of multicoloured, individually wrapped sweets that can be arranged and displayed at the curator’s discretion. The piece has an ‘ideal weight’ of 175 pounds – this was the weight of the eponymous Ross Laycock, Gonzalez-Torres’ boyfriend and the love of his life before he began to lose weight due to AIDS. ‘There was no other consideration involved except that I wanted to make an artwork that could disappear, that never existed, and it was a metaphor for when Ross was dying,’ Felix explained in an interview.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres was a Cuban-born American sculptor and installation artist whose sexuality informed his work in covert and conceptual ways. His art took a variety of forms, and he worked with assorted and eclectic mediums: billboards; stacks of posters; beaded curtains; strings of low-watt light bulbs hanging from walls or ceilings.

His most idiosyncratic and celebrated works are surely these ‘candy spills’ (‘candy’ works much better than ‘sweets’, don’t you think?). These pieces – nineteen artworks first exhibited between 1991 and 1993 – include chocolates and fortune cookies. Visitors are invited to take the sweets; the gallery is instructed to replenish the supply, although curatorial discretion can be applied as to when and how.

Felix didn’t merely reject the maxim of the gallery – ‘Do not touch the artworks’ – but reversed it, too: ‘Please, take this’. How many do you take – just the one? Or a cheeky handful, to share or save for a later date? Chocolates wrapped in foil; boiled sweets or bonbons: a minor gift from the absent artist. The small sweet treat dissolves, slowly, inside you. It becomes a part of you; the sugar flows through your blood, fuels you. A sweet treat on your tongue: you salivate and swallow. It’s childish and, simultaneously, somewhat erotic, sensual. This candy is part of a portrait of Ross, after all.

This act of anonymous sharing had heightened implications at the crux of the AIDS epidemic, before an effective drug treatment had been developed. People erroneously feared HIV could be spread by touch or through kissing. ‘Please, take this’.

These works survive and persist, creating a community – everyone who has ever, over thirty years and counting, taken and eaten a sweet is a part of something shared, part of Felix and Ross’s legacy. I’ve not yet visited or seen one of the candy spills. I have pages from two of Felix’s poster stack works rolled up in the corner of my living room. I still want a candy, though (well, two: one to eat and one to keep; a multisensory memory and a souvenir).

Recently, the Art Institute of Chicago – where the piece is kept – came under fire for removing reference to Ross and AIDS from the artwork’s caption. ‘How can the Art Institute engage in such a brazen act of queer erasure?’ Zac Thriffiley asked in the Windy City Times. Responding to the criticism, the Art Institute has since amended the text, once again including reference to Ross and his diagnosis with AIDS. Affirming their memory – both Felix and Ross – in the face of such erasure is vital.

This candy is more than just spilled confectionary. ‘It’s also about excess, about the excess of pleasure,’ Felix explained. ‘It’s like a child who wants a landscape of candies. First and foremost it’s about Ross. Then I wanted to please myself and then everybody.’ Felix died in Miami on 9 January 1996 due to complications arising from AIDS, aged 38.

Habit of Hands, by Megan Luddy O’Leary

Throughout the pandemic, I was surprised that the deepest grief I felt was not for the things I thought I would miss most – clubbing, sharing drinks at house parties, breathing communal air at sweaty gigs. Instead, what I yearned for above all was gathering friends around a table and cooking with them: watching them smash garlic, chop onions; talking as they cooked dinner, elusive subjects emerging with the steam from boiling pots. And so, when we emerged from a third lockdown in the autumn of 2021, I decided to examine the act of women cooking together in an artistic project titled Habits of Hands. I wanted to capture the act of the ‘habit of hands’ as discussed by the French philosopher Luce Giard – a way in which cooking becomes an act of communication between women in kitchens hazy with smoke, with the intimacy that cannot not be recreated over a video call.

I found inspiration in the Irish artist Jennie Moran, whose project Luncheonette I knew well, as it lived in the basement of my college, the National College of Art and Design (NCAD) in Dublin, where I spent every day from 2018 to 2021. Luncheonette wasn’t a short-lived installation – it was a functional canteen. In it, Moran provided warm porridge, cheap coffees topped with oat milk, raspberry scones, cheap soups topped with orzo, and Gubbeen cheese sandwiches to students, staff and wanderer-bys who climbed down into her refuge. I loved Luncheonette during my time in NCAD. My eventual college friendships grew out of the hospitality which Moran provided, over bowls of her roasted red-pepper soup. When I spoke to Moran in March 2022, she described how she imbues lifeless spaces with ‘dust’ – or a beautiful energy – by serving communal meals in them. Luncheonette was dynamic: it was built by everyone who entered it, creating and recreating itself every day.

Growing up, I routinely cooked in my family home, but once my sibling developed a life-threatening eating disorder there was no longer any magic in cooking. Instincts for taste became dulled in favour of brokering peace around meals. But through watching my friends cook during my time in college and eating at Luncheonette, my intuitions around cooking and eating were rewired. I absorbed not only cooking skills from my female friends but a belief that I should be nourished. A friend made me pasta. I watched her make a full bowl for me, because she cared about me, and a full bowl for herself because she cared about herself. And it was this language – the selection of the friendliest bowls, the chat around a kitchen – that I wanted to transmit into my project.

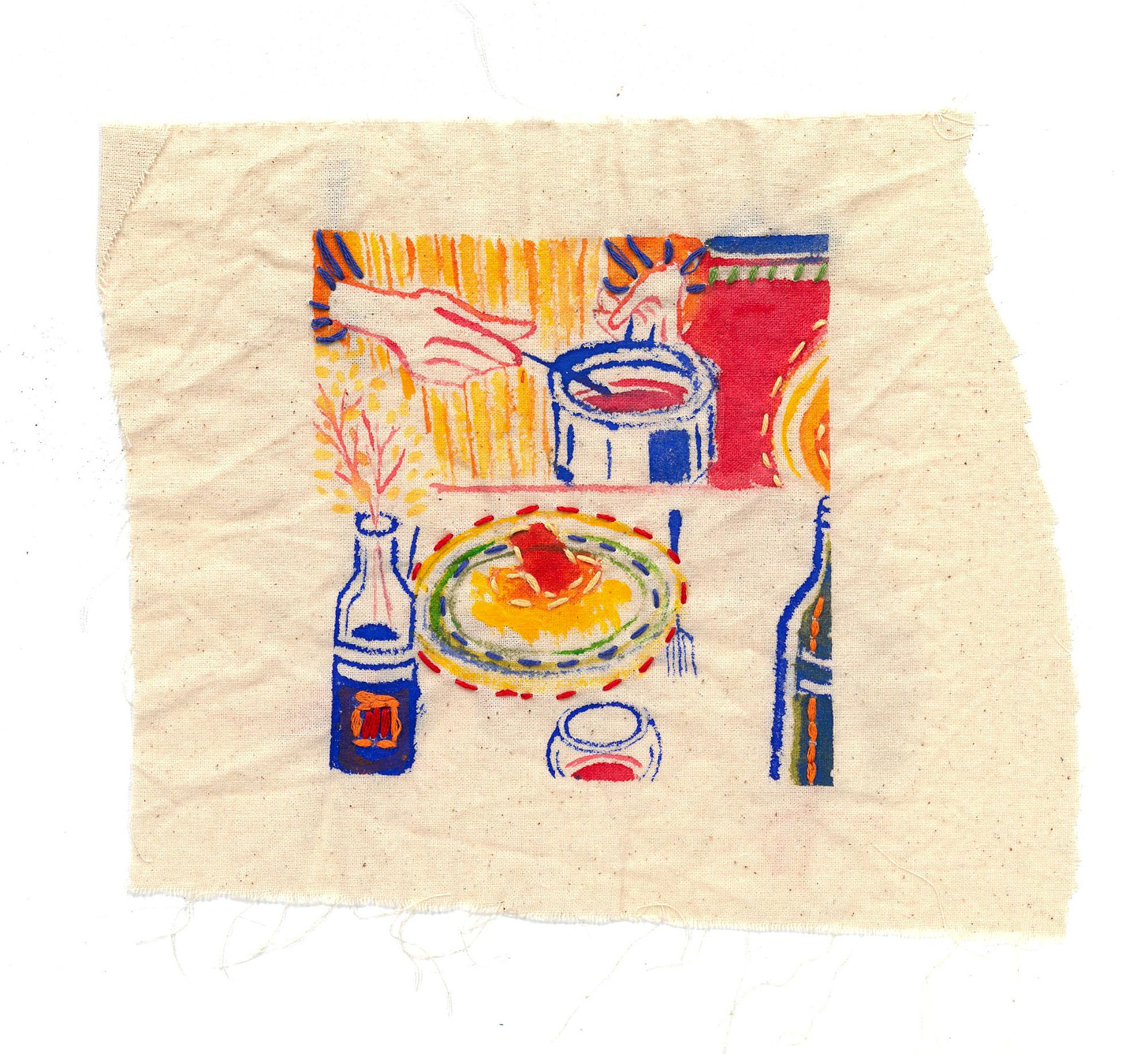

And so, in the spring of 2022, I made artefacts that reflected my personal history of cooking and the broader legacy of women cooking for one another. I embroidered a tablecloth with dinner conversations about cooking I had with my female friends. I created a ceramic series illustrated with information about the collective innovation of Mediterranean cuisines, which come from peasant women perpetually developing and passing on recipes. I conducted interviews and made oil-pastel drawings, all of which I gathered into an animated film. The film begins with a quote by Giard and moves on to conversations I shared – with my grandmother, friends and Moran herself – about relationships to domesticity and cooking. The looping of my hand-drawn animations reflects the beauty of this kind of cooking, which is always passed through family or friends like seamless legacies.

To watch The Kitchen Table, please scroll up to the start of the newsletter and press play.

To watch the animation Habits of Hands, please see below

Credits

Daniel Neofetou is a lecturer in critical and cultural studies at the University of Northampton. His most recent book Rereading Abstract Expressionism, Clement Greenberg and the Cold War was published in 2021.

Rachel Karasik is a former chef and current freelance project manager and producer working across food, tech, social innovation and systems change as part of the collective Iris+Birch. She also spends a lot of her time making both practical and impractical ceramics, which you can check out here.

Ruby Tandoh is a writer on food and culture whose work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Guardian, Vice, Taste, Eater, Vittles and more.

Louis Shankar is a writer and researcher focussing on queer life and culture based in London. They have recently started a PhD at UCL focusing on the work of the artist David Wojnarowicz.

Megan Luddy O’Leary is an award-winning freelance illustrator and artist from Ireland. She draws, paints, animates, writes, and makes things out of clay, collage and embroidery. Her work has been featured by Gill books and VIBE Magazine. Find her at meganluddy.cargo.site

Vittles is edited by Sharanya Deepak, Rebecca May Johnson, and Jonathan Nunn and proofed and subedited by Sophie Whitehead.

(No) Food and Drink in the Gallery